What do we do when we are not doing?

My grandmother tells me that her father used to sit under the cherry tree every afternoon (at least that’s how the intergenerational narrative goes) and not do anything for some time. Even though I never got to meet my great-grandfather, the image is painted clearly in my head and connoted with a certain idealising admiration.

This might be because on the continuum between ‘being’ and ‘doing’, I see myself as a ‘do-er’. It is also not by chance that I find myself in a performance company named ‘The Doing Group’. I gain a lot of my self-definition, daily structure and happiness from doing. So when forced to not do, for instance during the lock-down, I first start with working through what I thought were endless lists of things that I meant to do for a long time, like my tax returns – a coping mechanism to help myself avoid the reality of not doing. The list did eventually get shorter and still the lock-down persisted. As a group, we started to consciously turn our attention to ‘not doing’ in what we have called an online residency. Even though I felt fuelled by the idealised image of my great-grandfather under the cherry tree, the reality of attempting to relax into ‘not doing’ was anything but easy. Being deprived of a large (possibly too large) part of my personality as ‘theatre-maker’ and at the same time left with huge uncertainty about when or if at all this practice of live performance in a shared space and time will be possible again, I was stuck in a roller-coaster of emotions, feeling fatigue, denial, anger, bargaining, sadness and depression. I found these cycles of grieving aptly reflected in Lou Platt’s artist wellbeing blog, applying Kubler-Ross & Kessler’s book On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss onto grief within the arts during the pandemic. Lou Platt attests that as artists who are not able to follow their work, we are moving through five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. I saw my situation in response to half a year of intricately planned work projects being cancelled within 24 hours reflected in her reflections. However, I am still waiting for her last blog post of this series to come out, explaining ‘acceptance’ as the possibility of moving through grief.

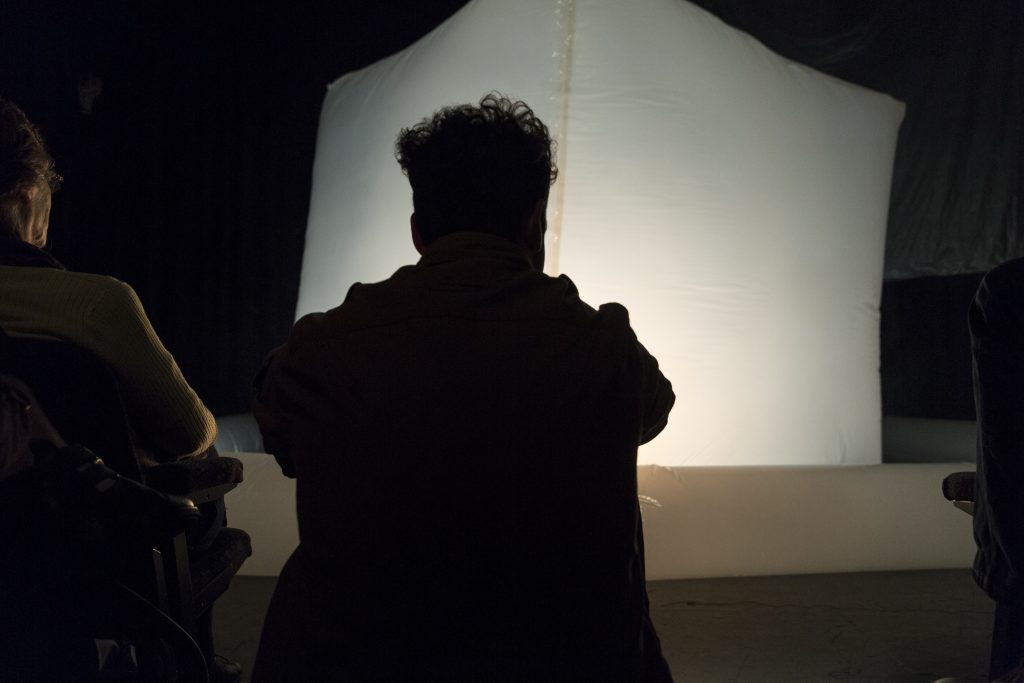

The day before the dress rehearsal of my experimental sound-theatre performance ‘How Deep Is The Sea’ in Innsbruck, we decided to cancel our premiere. At the time, the risk of spreading COVID-19 was still an unknown factor, whose possible severity we only realised in the preceding 24 hours. We still finished the lighting and last technical tweaks of the show and went ahead with a dress rehearsal for archival video recording, already knowing that it will not be premiered. It was a bizarre feeling, not to have the moment of relief when sharing the results of many months of intense work with an audience. This gave me a different perspective on the ‘normal’ production realities within performing arts where in the weeks leading up to the premiere nothing seems more important than the show and the pressure increases day by day. The stress levels are high and our bodies are exploited through sleep deprivation and long non-stop working days. But where does this pressure even come from?

When we took everything down a day before the cancelled premiere and start of the strict lock-down, surprisingly, I did not feel disappointed in any way. At first there was a bit of uncertainty and disorientation as the usual pattern of rehearsing to perform was broken and the moment of release was missing. Why do we depend on audiences to applaud, critics to review and work to ‘land’? For myself, I figured that there was a need of external approval, but what for? So, I started to personally appraise my own work more deeply. When I was not able to perform for an audience, I reflected and felt through the work myself. I took the time to reflect and listen. I was surprised to start hearing the quieter voices that are usually drowned in all the noise of perpetual doing.

In her blog posts, Lou Platt also suggests that there is a grammatical imbalance between ‘being’ and ‘doing’ since there is no equivalent of the active subject ‘do-er’ – a ‘be-er’? Was my great-grandfather under the cherry tree a ‘be-er’? Other anecdotes of him with his horse and cart, in his workshop or on camping trips paint a different image of him, also as a doer. I gain hope and I ask myself how can I become a be-er or how can I work on the be-er in me? Quickly I realise that the question underlying this is: how do you do ‘being’? – in other words: What do you do when you just want to ‘be’? I must laugh since the doer in me already hijacked the ‘not-doing-just-being’ project again. I smile at myself and allow this to happen. I ask my grandmother what her father used to do when he was not doing anything under the cherry tree? She does not take this as a weird question and responds: ‘Every afternoon he was sitting under the cherry tree, listening to the birds, thinking, whistling and sometimes snoozing with his straw hat pulled down over his face.’ Hence, I am gentle with myself and observe what I do when I try to ‘not do’: sleeping, sitting, breathing, thinking, go for walks or just walk around aimlessly, watch birds, listen to the birds and imitate their calls, chat to neighbours who I have not spoken to in many years in the street (of course with 2m distance). Simply, I take time for what comes up, acknowledge and take care of my surroundings.

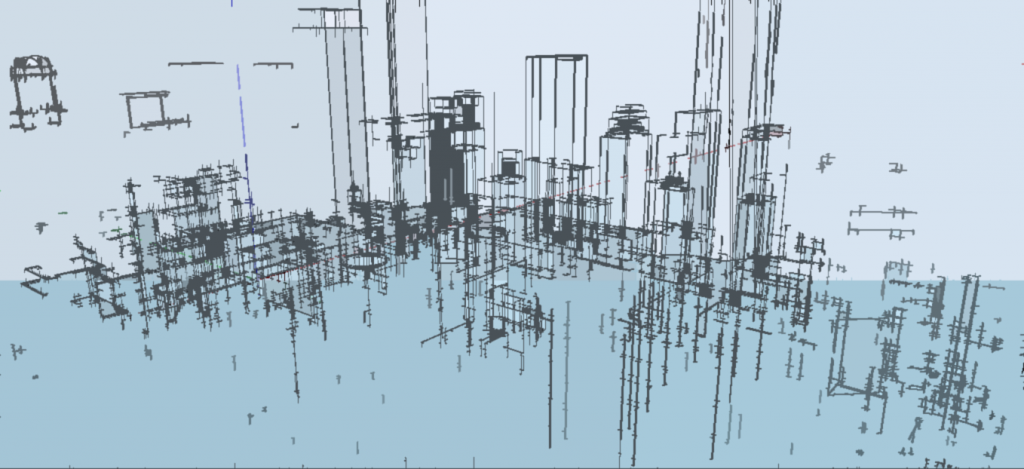

In our ‘not doing’ online residency as The Doing Group, we take time to ask ourselves as individuals and artists but also as a company and a group of friends, what we do when we are ‘not doing’. In different formats we have been reflecting, talking, thinking. We asked ourselves what the research question of our first performance ‘Rain is Liquid Sunshine’, what futures can be imagined once the idea of progress is drained away, might mean nowadays, how we can think without questions, how we can work on a shared project with individual timelines, what it means to be ‘not doing’ but feeling, how we learned our whiteness and how we can imagine invisible futures. Another aspect that developed along the way, is a weekly Embodied Yoga Principle practice led by our group member Hannah. In this physical and emotional meditation, we explore through our bodies, how we feel in certain roles or with certain emotions, where we know them from and where we feel the need for more of them in our lives. This allowed me to really feel the complementary, interconnected and interdependent nature of opposites as it is embedded in the practice through the Ancient Chinese dualism of YIN, representing receiving, acceptance and consent, and YANG, associated with agency, giving and offering.

In our online residency, we have been cultivating a practice of ‘not doing’ as a dialectically complementary to our ‘normal’ practice of doing. We consciously are taking time for what comes up, focusing on the process and trusting it to unfold. The total suspension (cancellation and in the best case postponement) of our work caused a process of grief but also opened up a time for time – a time for being.

I was privileged to be able to attend a huge ceremony of Indigenous leaders and shamans at the Isla del Sol (Island of the Sun) on Lake Titicaca in Bolivia on December 21st, 2012. Marking the end of the Mayan calendar, Indigenous people celebrated the beginning of a new period in human history instead of the end of the world. In this turn of times, the dark period of ‘Macha’ or ‘no time’ which had started with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in America was followed by ‘Pachakuti’ as ‘a time for time’, overcoming capitalism, the ego and the destruction of the earth. Could it be that the calculations were about 7 years off (or it has taken us 7 years and a pandemic to realise) and now we are feeling the new age ‘Pachakuti’ where we have time to take time, where the injustice and exploitation of capitalism and white supremacy are finally being overcome and the trauma of colonialism and slavery are being healed?

So in our group, we try to take time for time and include being in our doing, try to find ways to be ‘be-ers’ as well as doers, make time for being while doing and attempt to bridge the dialectical opposites of the yin-being and yang-doing, so that one cannot be thought without the other.

However, similar to the admiration for my great-grandfather under the cherry tree, I acknowledge that we are also idealising this ‘not doing’ from a place of utmost privilege of our education and economic stability to even be able to take time for ‘not doing’. I am thankful for this generosity as I also see problems with the phrase. The German translation of ‘not doing’ for instance would probably be found somewhere between ‘nichts tun’ (doing nothing) and ‘untätig sein’ (being not-doing) which might also point towards the semantic imbalance between being and doing that Lou Platt had mentioned and already bridges the not-doing with the being. Not doing but being. However, in German both of these versions and especially ‘untätig sein’ (being not-doing) have a problematic political connotation of not doing anything, for instance against injustice and racism: Just watching and being a bystander, not intervening or not going to the protests. This notion of ‘not doing’ is obviously problematic at the moment in response to the violence and injustice towards Black, Indigenous and People of Colour all around the world but especially prominent in America at the moment. Not doing anything about this historical injustice and trauma in the sense of being ‘untätig’ (not-doing) or even ‘tatenlos’ (without deeds) means being complicit with white supremacy. However, also in this semantic analysis of the political dimension of ‘not doing’, an inherent ableism might be at work of who might even be in the position to turn up and do something. I see a huge part to be done in our society and within myself by tackling our inability to hold space and reflection around race – building white stamina, as Resmaa Menakem calls it. Acknowledging the white inabilities around race rather than insisting on the deeds which remain in the logic of perpetual doing and the unbroken white agency which sometimes (and especially on social media) seem to have mainly a performative dimension of a speech act: I state that I am anti-racist, therefore I am. In such instances deep personal self-reflection, which conventionally lies more on the spectrum of being than doing, might be more of an active anti-racist work than the active self-proclamation. Maybe there is a possibility for a more dialectical Yin-Yang understanding of ‘not doing’ that also accounts for this problematics and recognises the activity in the reflecting and taking time.

Thinking of all the work and travelling I would have done until the autumn gives me a fright now. In the same way as it was hard to get used to the thought and reality of all these ideas and plans not taking place as planned, we want to make it difficult for ourselves to fall back into these patterns of unidirectional productivity and efficiency. Considering the possibility that things could also just not take place offers the chance to include the ‘not doing’ in the conception and execution of the doing. Keeping the cherry tree in mind, while our diaries might threaten to fill up again, might allow for more time. Maybe this is part of the ‘acceptance’ that we need as artists to move through the grief of the last months.

TDG.peter